Vertical Cities: The Urban Future Imperative

The unrelenting trajectory of global urbanization necessitates a fundamental re-evaluation of how human settlements are conceived, built, and sustained. With the world’s urban population expected to swell by billions over the next few decades, the conventional two-dimensional expansion of cities—urban sprawl—has become economically, environmentally, and socially bankrupt. The inevitable, architecturally ambitious solution lies in the development of Vertical Cities: self-contained, hyper-dense, and multi-functional megastructures designed to concentrate all necessary urban activities within a dramatically reduced horizontal footprint. This paradigm shift, often driven by the intersection of advanced engineering and ecological urbanism, represents the most significant architectural and planning challenge of the current era. This exhaustive analysis delves into the intricate technological, structural, and societal components that establish the Vertical City not merely as a concept, but as the mandatory future of efficient and sustainable metropolitan living.

I. Conceptualizing the Three-Dimensional Metropolis

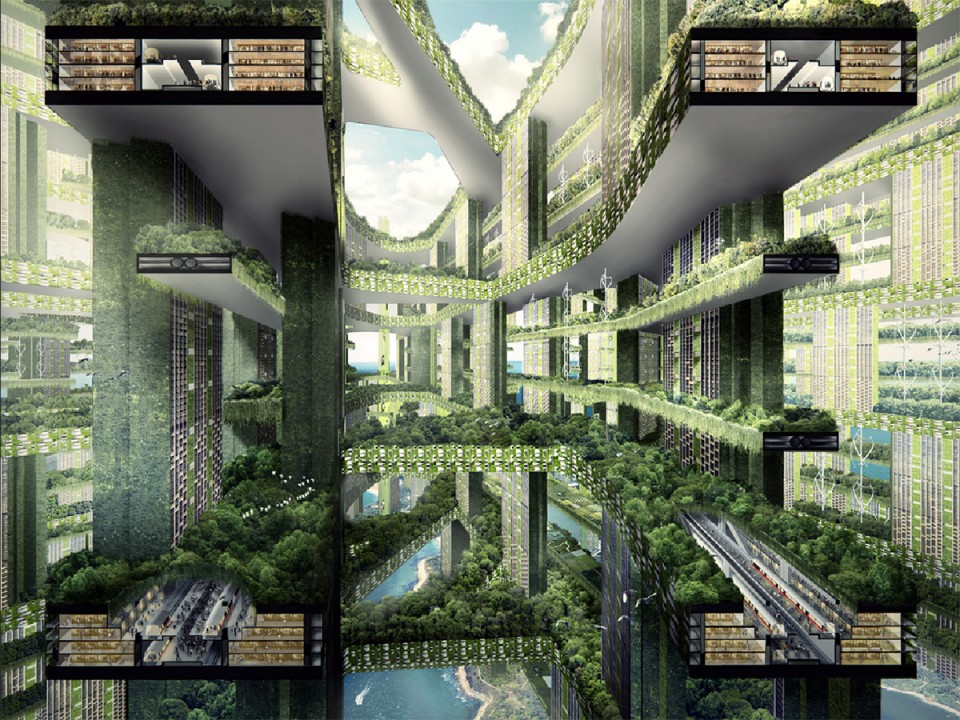

The term “Vertical City” goes far beyond a collection of tall buildings. It describes a singular, intensely integrated structure, or a closely linked cluster of structures, that functions as a complete urban ecosystem. It is a true third dimension of urban planning, where vertical transportation and utility distribution become the new ‘streets’ and ‘subways.’ The core principle is to create live-work-play-grow zones layered one upon the other, minimizing the time, distance, and energy required for daily life.

The Architectural Mandate for Verticality

The architectural design of a Vertical City is governed by constraints utterly different from those of conventional planning. The design must accommodate the complex requirements of diverse functions—from specialized manufacturing floors to high-end residential units—all within a single building envelope.

A. The Multi-Core System: To manage the massive volume of vertical movement, a single central core is insufficient. Vertical cities often employ multiple structural and transportation cores, each serving specific functional zones (e.g., residential, commercial, industrial) to prevent traffic bottlenecks and ensure rapid transit between levels.

B. Stratified Zoning and Segregation: Traditional urban zoning (residential separated from retail, separated from industry) is applied vertically. Planners must strategically layer these zones, ensuring minimal disruption between functions—for example, buffering residential areas from high-vibration manufacturing floors with intermediate mechanical or recreational levels.

C. Bridging and Connectivity: The design frequently incorporates sky bridges, shared atriums, and mid-level plazas at defined intervals. These spaces, sometimes spanning multiple structures, serve as elevated public parks and community anchors, acting as the horizontal ‘neighborhood streets’ that are crucial for social interaction and psychological well-being.

D. Megastructure Scale and Construction Sequencing: These projects require innovative construction methodologies, such as top-down or jump-form construction, to safely and rapidly build the super-structures. The complexity dictates that construction of one zone (e.g., lower commercial floors) may be completed and operational while upper zones are still under construction.

II. Environmental Stewardship Through Compression

The compelling argument for vertical cities rests heavily on their superior environmental performance compared to equivalent populations spread out horizontally. This concentration is key to mitigating climate change impacts associated with urban sprawl.

1. Land Use and Ecological Impact

Verticality fundamentally solves the problem of urban sprawl, which devours natural ecosystems and prime agricultural land.

A. Preservation of Green Belt Land: By minimizing the land footprint (the land at the base), billions of square feet of developable area can be preserved in its natural state, supporting local biodiversity and ecosystem services like natural water filtration and carbon sequestration.

B. Reduced Infrastructure Sprawl: Low-density development requires hundreds of miles of piping, wiring, and roads, leading to massive energy loss and construction cost. Vertical compression allows infrastructure to be short, direct, and centralized, leading to near-zero transmission loss in critical utility systems (water and power).

C. Enhanced Water Cycle Management: The minimal ground footprint combined with advanced, closed-loop systems (detailed below) dramatically reduces the discharge of pollutants into natural waterways. Extensive rooftop and mid-level gardens manage surface runoff locally.

2. Radical Resource Self-Sufficiency

The compact nature of the vertical city allows for unprecedented levels of resource localization and efficiency.

A. Integrated Vertical Agriculture (VFA): Dedicated, climate-controlled floors or optimized façade greenhouses host vertical farms. VFA dramatically reduces water consumption (up to 95% less than field farming) and completely eliminates the logistical and carbon costs of long-distance food transport. This creates food security directly within the urban mass.

B. Closed-Loop Water and Waste Recycling: Vertical cities necessitate micro-utility grids. This includes advanced tertiary treatment plants within the structure, recycling nearly all greywater and even treated blackwater for industrial, cooling, and irrigation purposes. Solid waste is often processed through on-site, small-scale waste-to-energy conversion systems (e.g., plasma gasification), effectively neutralizing landfill dependency.

C. Optimized Energy Production and Management: The massive façade area is exploited for energy capture.

High-Efficiency Building Envelope: Employing triple-pane, intelligent glass that dynamically adjusts opacity minimizes solar gain and heat loss, drastically reducing the thermal load on HVAC systems.

Building Integrated Photovoltaics (BIPVs): Facade panels are utilized as solar energy generators, providing a substantial portion of the structure’s electrical needs. Furthermore, the height offers access to consistent wind patterns, making integrated vertical axis wind turbines viable additions.

III. Overcoming the Engineering and Human Hurdles

While the vision is compelling, the technical implementation and the human factor present substantial, interwoven challenges that must be addressed through innovation.

1. Structural Integrity at Extreme Scales

Building structures that withstand extreme lateral forces (wind and seismic activity) at heights of 500 meters and beyond requires pushing material science and structural dynamics to their limits.

A. Advanced Material Science: Reliance on ultra-high-strength steel and fiber-reinforced, high-performance concrete (FHPC) is mandatory. These materials allow for smaller structural elements capable of carrying higher loads, reducing the overall weight and mass of the structure.

B. Dynamic Damping Systems: Stability and occupant comfort are maintained through sophisticated active and passive structural controls. This includes massive, computer-controlled Tuned Mass Dampers (TMDs), which counteract building sway caused by wind loads by oscillating an enormous counterweight, or hydraulic control systems embedded throughout the structure.

C. Core-and-Outrigger Systems: The structural framework relies on a highly rigid central core connected to perimeter columns via outrigger trusses at specific height intervals. This configuration transfers lateral forces away from the core and distributes them over the entire building footprint, greatly increasing stiffness.

2. Mitigating the Psychological Impact of Density

Concentrating thousands of residents vertically introduces potential psychological stressors related to height, crowding, and disconnection from nature. Architectural design must deliberately counteract these effects.

A. Biophilic Integration and Vertical Parks: The concept of Biophilic Design—integrating natural systems and views into the built environment—is non-negotiable. Designing large, wind-protected vertical parks or “sky forests” at strategic intervals provides necessary access to nature and fresh air, serving as decompression zones and visual anchors.

B. Acoustic Management: High-density living demands superior acoustic separation between residential, commercial, and transportation layers. Advanced soundproofing materials and mechanical decoupling of different functional zones are essential to prevent noise pollution from vertically traveling through the structure.

C. High-Speed, Zoned Elevator Systems: To defeat the psychological friction of long commutes within the building, destination dispatch and express zonal elevators are crucial. These systems minimize stops and wait times, essentially transforming the internal vertical movement into a highly efficient, multi-level metro system.

IV. The PropTech Imperative: Operationalizing Complexity

A Vertical City is, at its heart, the world’s largest machine. It cannot be managed by conventional human teams or manual systems. PropTech (Property Technology) provides the essential AI and IoT layer necessary to manage the extreme complexity, ensuring efficiency, safety, and comfort.

1. The Smart City Operating System

At the heart of the vertical metropolis lies a singular, centralized, AI-driven Building Operating System (BOS) that integrates all core functions.

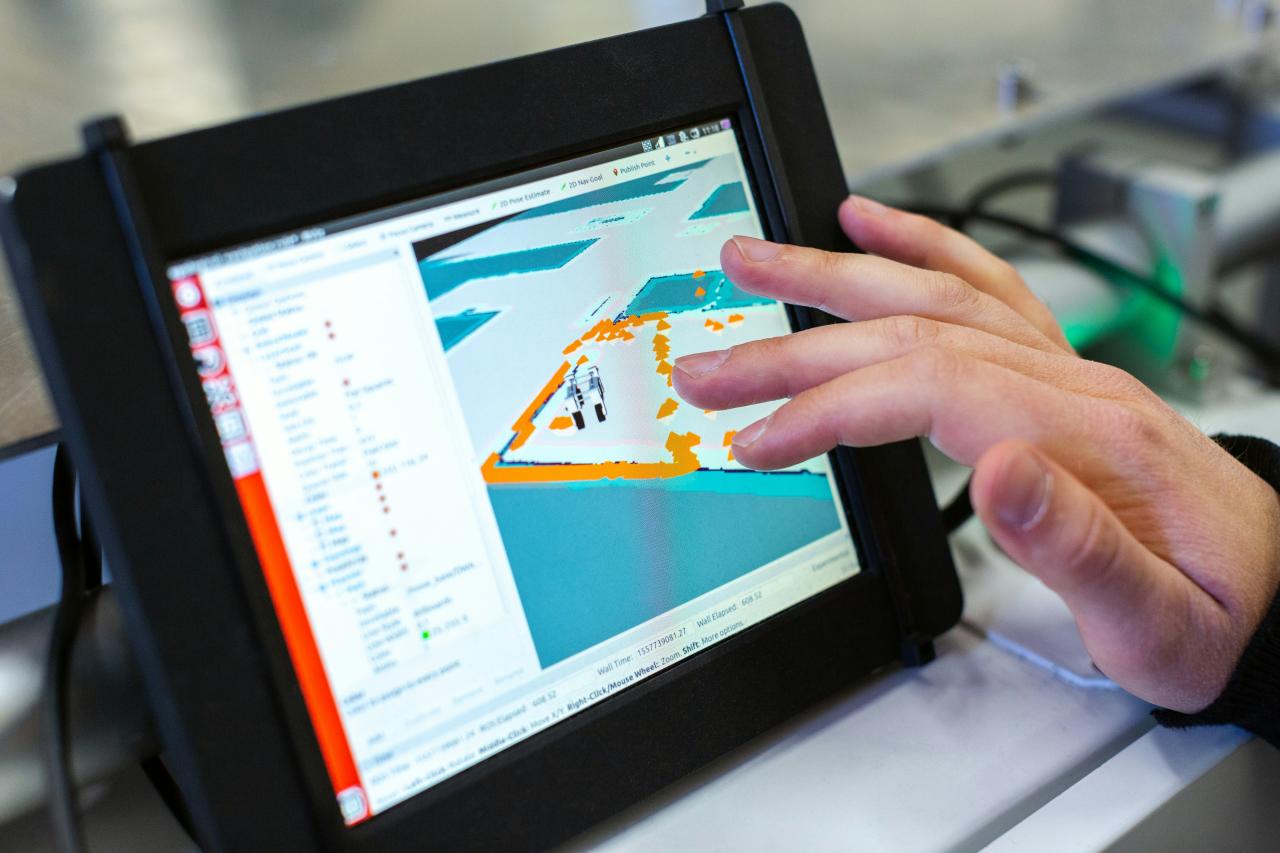

A. Sensor Network and Digital Twin: The BOS relies on thousands of IoT sensors embedded in every element—from the structural columns to the plumbing—continuously feeding real-time performance data into a Digital Twin. This virtual replica allows operators to simulate changes, predict failures, and test emergency responses in a safe environment.

B. Predictive Maintenance and Fault Diagnostics: Using Machine Learning, the BOS constantly analyzes data patterns to predict when a critical system (e.g., an elevator motor, a cooling pump, a BIPV panel) is likely to fail. This enables maintenance to be scheduled proactively, minimizing disruption and ensuring near-100% uptime for all essential services.

C. Dynamic Environmental Control: The system manages the building’s massive HVAC and lighting load dynamically. It adjusts temperature and illumination based on real-time occupancy detected by integrated sensors, external weather conditions, and energy pricing, achieving unparalleled energy savings.

2. Logistics and Waste Management Automation

The flow of goods and waste in a vertical structure must be entirely automated to prevent traffic and logistical chaos.

A. Automated Guided Vehicles (AGVs) and Robotics: Automated carts and drones manage the delivery of parcels, internal mail, and small supplies from ground-level receiving docks to designated floor hubs, ensuring minimal human intervention and rapid turnaround.

B. Pneumatic Waste Collection (PWC): Vertical cities must employ vacuum waste systems. Tenants deposit trash into chutes, which are connected to sealed tubes that pneumatically transport waste and recycling to a centralized, subterranean processing center, entirely eliminating the sight and smell of garbage collection within the public areas.

C. Vertical Food Chain Integration: The BOS directly manages the climate, nutrient delivery, and lighting cycles for the internal vertical farms, optimizing yield and scheduling the harvest for immediate distribution to the internal commercial kitchens and grocery outlets.

V. Economic and Governance Models

The colossal investment and intense density of a vertical city mandate new economic and governance structures to ensure financial viability and social harmony.

1. Unique Economic Value Proposition

The value proposition of a vertical city shifts from “location” (proximity to the city center) to “self-containment” (proximity to everything within the structure itself).

A. Economic Density and Clustering: Concentrating different, often synergistic, businesses (e.g., biotech labs, research universities, financial trading floors) within the same envelope fosters unparalleled levels of innovation and collaboration, creating a massive economic multiplier effect.

B. Long-Term Operational Cost Savings: While initial construction costs are significantly higher than traditional development, the long-term operational costs—driven down by localized energy generation, advanced resource recycling, and AI-driven predictive maintenance—are substantially lower, justifying the upfront capital expenditure.

C. New Revenue Streams from Services: The management entity can generate additional revenue by providing integrated services—energy, water, high-speed telecom, and even food—to its tenants and residents, moving the financial model beyond simple rent collection to a Service-as-a-Utility model.

2. The Micro-Municipality Governance Model

Managing tens of thousands of people in a privately owned, highly controlled environment requires a hybrid legal and administrative framework.

A. Community Regulations and Bylaws: The management body of the vertical city must adopt a comprehensive set of bylaws that govern everything from noise levels and waste disposal to shared amenity use and commercial signage. These rules essentially constitute the city’s internal regulatory code.

B. Integrated Security and Emergency Services: Security, fire safety, and internal medical emergency response teams must be hyper-localized and integrated into the structure’s BOS. Response times are measured in seconds, not minutes, requiring specialized training for vertical deployment and disaster management.

C. Stakeholder Engagement and Dispute Resolution: Clear, transparent mechanisms for resident and commercial tenant feedback and dispute resolution are crucial to maintaining social cohesion within the dense, high-pressure environment.

VI. The Future Trajectory: Hyper-Integrated Urbanism

Vertical Cities are not the endpoint of urban evolution, but the critical transition phase. The future will see these structures becoming even more integrated with their surrounding environments.

A. Modular and Adaptable Architecture

Future vertical city designs will incorporate modular, adaptive architecture where internal structural components (e.g., walls, utility connections) can be rapidly reconfigured to meet changing economic demands, allowing for rapid conversion of office space to residential units or vice versa, ensuring the structure remains economically relevant for centuries.

B. Regional Connectivity

Vertical cities will become regional hubs, seamlessly integrating with external high-speed transport networks—such as high-speed rail, regional APMs, and drone delivery systems—to connect residents with the broader geographic region, maximizing the economic catchment area without contributing to traditional road congestion.

C. The Human-Centric Design Focus

As the technical challenges are conquered, the focus of architecture and urban planning will shift almost exclusively to the human experience. Future vertical cities will be designed not just for structural efficiency but for maximum human flourishing, emphasizing natural light, acoustic comfort, psychological connectivity, and universal access to green, communal spaces, setting the standard for sustainable, high-density living.

The Vertical City is the definitive architectural response to the urban crisis. It demands an unprecedented fusion of advanced engineering, data science, and holistic urban planning. By leveraging PropTech to manage its inherent complexity and prioritizing ecological resilience, the ascent towards vertical urbanism is the only pathway to accommodate a thriving, growing global population while safeguarding the planet’s finite resources. The future of the city is tall, smart, and profoundly integrated.