The world’s urban centers, which are currently home to over half of the global population and generate the vast majority of its economic output, stand directly on the front lines of the escalating climate crisis, facing an immediate and intensifying barrage of threats ranging from rising sea levels and devastating coastal erosion to more frequent, severe heatwaves and erratic, torrential rainfall leading to catastrophic inland flooding.

Historically, city planning focused predominantly on efficiency and growth, viewing environmental risks as sporadic events to be managed reactively, but this antiquated approach is no longer tenable in an era defined by accelerating climatic instability and the increasing likelihood of high-impact, low-probability events that can instantly paralyze critical infrastructure and displace millions of residents.

The inherent concentration of people, assets, and complex, interconnected systems within a limited geographic footprint means that climate hazards amplify vulnerabilities within cities, threatening not just physical structures but also the social, economic, and institutional stability that underpins urban life.

Therefore, Climate Resilience has emerged as the most critical priority for 21st-century urban governance, requiring a proactive, holistic, and long-term planning paradigm that shifts the focus from simply reducing carbon emissions (mitigation) to fundamentally redesigning and hardening urban systems so they can effectively anticipate, absorb, recover from, and successfully adapt to the inevitable disruptions caused by a rapidly changing global environment.

Pillar 1: Understanding Urban Climate Vulnerabilities

Identifying the primary ways climate change attacks city systems.

A. Physical and Infrastructure Threats

The direct damage to the built environment.

Water Hazards: This includes coastal inundation from sea-level rise and flash flooding from extreme precipitation, threatening basements, transport networks, and underground utilities.

Thermal Hazards: Increased frequency and intensity of heatwaves pose massive risks to power grids (due to higher cooling demand), road surfaces, and public health, especially in dense, high-rise areas.

Wind and Storm Hazards: Stronger, more frequent tropical cyclones and wind events inflict structural damage on buildings, disrupt supply chains, and cause widespread power outages.

B. Socio-Economic and Institutional Threats

The impact on people and governance.

Public Health Crisis: Extreme heat and air pollution exacerbate respiratory and cardiovascular diseases, while floods contaminate water supplies, leading to outbreaks of waterborne illnesses.

Economic Disruption: Climate events cause direct property losses and lead to long-term business interruption, driving up insurance costs and potentially leading to permanent job losses.

Equity and Justice: Climate risks disproportionately affect low-income neighborhoods and marginalized communities, which often lack adequate housing, cooling access, and insurance coverage, deepening social inequalities.

C. Systemic Interdependencies

The complex, domino-effect risks within a city.

Energy and Transport: A severe flood that damages a main power substation can immediately shut down the subway system, preventing essential workers from reaching hospitals, illustrating a critical failure cascade.

Food and Water Supply: Extreme drought can impact regional agricultural output, leading to food price spikes, while simultaneously stressing the municipal water supply and forcing severe usage restrictions.

The Single Point of Failure: Resilience planning must actively identify and eliminate single points of failure in critical infrastructure, such as vital bridges or primary power distribution centers, which can cripple the whole city if damaged.

Pillar 2: The Core Pillars of Climate Resilience Planning

Establishing the strategic framework for urban adaptation.

A. Proactive Risk Assessment and Mapping

Understanding exactly what might happen and where.

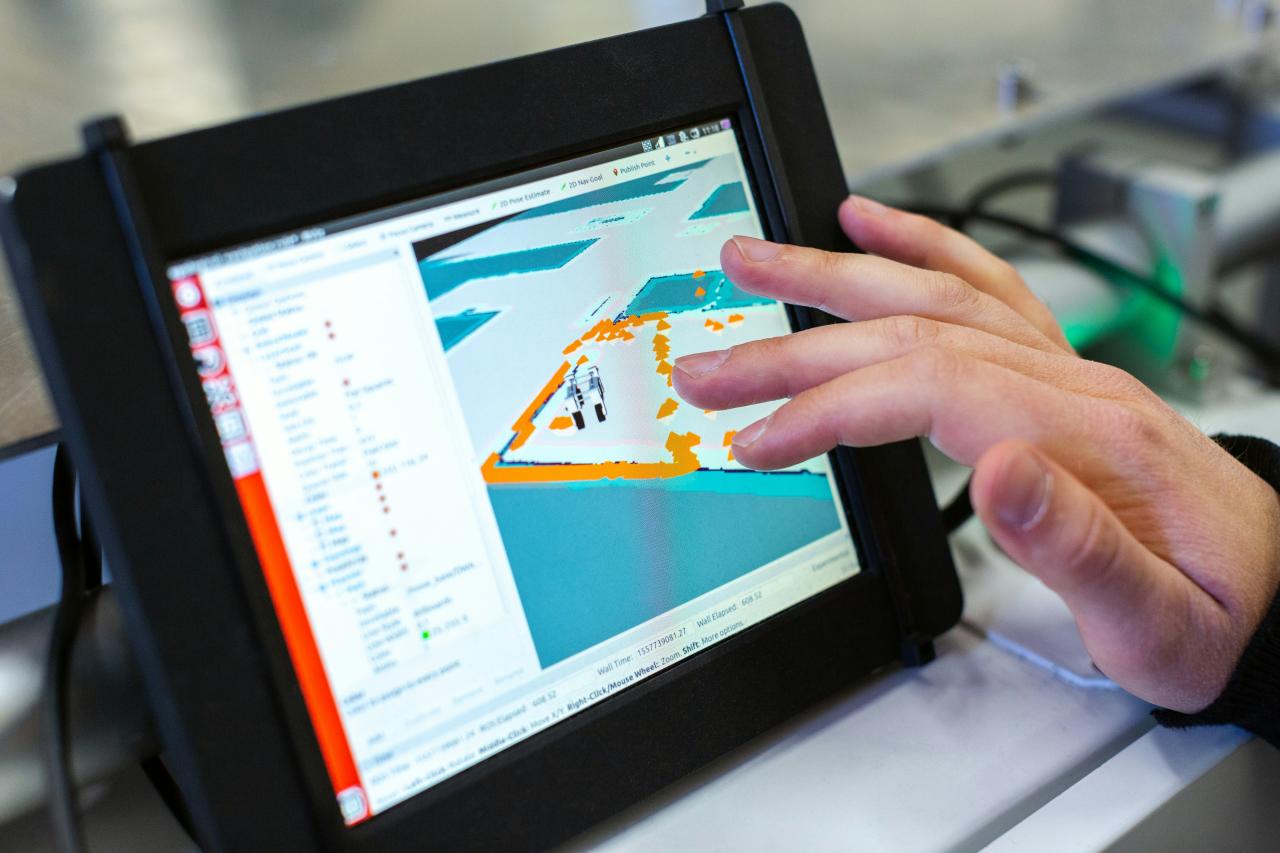

Vulnerability Mapping: Utilize advanced GIS (Geographic Information System) tools to map current assets and populations against future climate projections (e.g., a 100-year flood plain in 2050).

Scenario Planning: Develop plausible worst-case scenarios (e.g., a 4-degree Celsius temperature rise, Category 5 hurricane strike) and analyze how city systems would perform under those extreme stresses.

Data Integration: Resilience requires continuously integrating real-time weather data, infrastructure sensor readings, and population density information to monitor vulnerabilities and adjust defenses dynamically.

B. Adaptive Governance and Institutional Capacity

Ensuring the city government can respond flexibly.

Cross-Sector Collaboration: Break down traditional silos by creating mandated working groups that include officials from Transportation, Public Health, Energy, and Housing to coordinate resilience efforts.

Flexible Budgeting: Establish dedicated, flexible adaptation funds that can be rapidly deployed for emergency repairs or incremental upgrades without being bogged down in lengthy annual budget cycles.

Public Awareness: Implement robust public education and warning systems, ensuring all citizens know their risks, evacuation routes, and how to access emergency services during a climate event.

C. Integration of Natural and Built Solutions

Combining “gray” engineering with “green” ecosystems.

Green Infrastructure (GI): Use nature-based solutions like rain gardens, bioswales, and permeable pavementsto naturally absorb stormwater and reduce runoff, easing the burden on conventional “gray” storm drains.

Ecosystem Services: Protect and restore coastal wetlands, mangrove forests, and dunes which serve as natural, self-sustaining buffers against storm surge and sea-level rise, often more effectively than concrete seawalls.

Hybrid Defenses: Design hybrid defense systems that strategically combine hardened infrastructure (like floodwalls) with flexible natural elements (like parks and restored floodplains) for multi-layered protection.

Pillar 3: Resilient Infrastructure Design and Hardening

Specific strategies to make physical systems shock-proof and adaptable.

A. Water Management and Flood Control

Rethinking drainage systems for extreme rainfall events.

Distributed Retention: Move away from centralizing flood control and instead create a network of distributed stormwater retention ponds, reservoirs, and green roofs across the city to manage water where it falls.

Elevating Critical Assets: Require new critical infrastructure (power stations, data centers, hospitals) in flood-prone areas to be built above projected future flood levels (e.g., the 500-year flood line plus a climate change factor).

Blue-Green Networks: Design city parks, streets, and open spaces as integrated “blue-green” networks that double as overflow floodways during extreme rain events, preventing damage to residential areas.

B. Energy and Utility Resilience

Ensuring power and communication continuity after a shock.

Decentralized Power: Promote the transition to decentralized, distributed energy sources (e.g., solar microgrids, community battery storage) that can continue to operate and power critical services even if the main grid fails.

Undergrounding Utilities: Invest in moving essential utility lines (power and communication cables) underground where they are protected from high winds, falling debris, and intense surface heat.

Smart Grid Technology: Implement smart grid systems that automatically detect, isolate, and rapidly reroute power around damaged sections, minimizing the duration and extent of outages.

C. Resilient Transportation Networks

Keeping the city moving despite physical disruptions.

Diversified Routes: Plan for redundant and diversified transportation routes (roads, rail, ferries) so that the loss of one key route does not paralyze the entire movement of goods and people.

Hardened Bridges and Tunnels: Conduct structural assessments and harden critical bridges and tunnels against seismic events, high winds, and corrosive saltwater intrusion from sea-level rise.

Emergency Transit: Design public transport systems to accommodate emergency services and evacuation routes, ensuring quick access and egress during crises.

Pillar 4: Social Resilience and Urban Equity

Focusing on the people and communities that hold the city together.

A. Addressing the Urban Heat Island Effect

Protecting vulnerable populations from lethal heat.

Aggressive Tree Canopy Expansion: Implement policies to aggressively increase the urban tree canopythroughout all neighborhoods, as mature trees provide crucial shade and evaporative cooling.

Cool Roofs and Pavements: Mandate or incentivize the use of light-colored, reflective roofing materials (“cool roofs”) and lighter pavement materials to reflect solar radiation rather than absorbing it.

Cooling Centers: Establish a network of designated, accessible, and reliably powered cooling centers in libraries, schools, and community centers during heatwaves, particularly serving the elderly and those without home air conditioning.

B. Affordable and Resilient Housing

Securing dwellings against climate shocks and economic pressures.

Climate-Resistant Design: Mandate that all new housing construction incorporate climate-resistant designs(e.g., storm shutters, higher window ratings, flood-resistant materials) based on future projections.

Retrofitting Programs: Create subsidized programs for low-income homeowners and rental providers to retrofit existing vulnerable structures (insulation, water sealing, better drainage) against current and future climate risks.

Protecting Tenants: Implement anti-displacement policies and rent controls in areas slated for resilience investment to prevent low-income residents from being priced out after neighborhood improvements.

C. Community-Led Resilience Initiatives

Harnessing local knowledge and self-organizing capacity.

Localized Resilience Hubs: Designate and equip neighborhood community centers or schools as local resilience hubs that provide decentralized aid, information, power, and shelter during city-wide crises.

Training Community Leaders: Invest in training local neighborhood leaders and block captains in basic emergency response, communication protocols, and resource distribution to enhance rapid local response capability.

Cultural and Social Capital: Recognize and support local social networks and neighborhood associations which are critical sources of social capital and provide the fastest, most effective form of mutual aid during a crisis.

Pillar 5: Financing and Governing Future Resilience

The mechanisms for making long-term adaptation financially viable and politically sustainable.

A. Innovative Financing Mechanisms

Securing the large-scale investment required for adaptation.

Climate Bonds: Issue municipal “climate bonds” or “resilience bonds” to attract private and institutional capital specifically for high-impact adaptation projects like sea walls, microgrids, and green infrastructure.

Value Capture: Implement value capture mechanisms (e.g., special assessment districts) that channel the increased property value resulting from major resilience investments (like a new subway line or coastal protection) back into funding the project’s debt.

Risk-Based Insurance: Work with the insurance industry to develop climate-risk-based insurance incentives, offering lower premiums for homes and businesses that demonstrably invest in hardening their properties.

B. Establishing a Resilience Chief Officer (CRO)

Centralizing authority and accountability.

Mandate and Authority: Appoint a Chief Resilience Officer (CRO) with cabinet-level authority, whose primary mandate is to coordinate all resilience efforts across disparate city departments and break down bureaucratic barriers.

Integrated Planning: Ensure the CRO is responsible for integrating climate risk analysis into all major municipal planning documents (e.g., zoning codes, capital improvement plans, and comprehensive city master plans).

Long-Term Accountability: The CRO provides a single point of accountability to report to the public and elected officials on the city’s progress against its long-term adaptation goals.

C. The Adaptive Pathway Approach

Planning for uncertainty with flexibility.

Phased Investment: Instead of building a single, massive, fixed solution today, adopt “adaptive pathways” planning, which involves a series of sequenced, phased, and reversible investments triggered by specific climate metrics.

Trigger Points: Define clear future “trigger points” (e.g., “when the average sea level rises by X inches, we will execute Phase 2: Building the flexible barrier system”).

Avoiding Maladaptation: This approach helps avoid maladaptation—investing huge sums in a rigid solution that later proves ineffective—by maintaining flexibility and allowing the city to adjust its strategy as new climate data emerges.

Conclusion: Securing a Viable Urban Future

Climate resilience is not an optional environmental luxury; it is the fundamental, non-negotiable strategic bedrock upon which the entire economic viability and social stability of the 21st-century city must be deliberately built.

Urban centers face a complex matrix of escalating physical threats, ranging from catastrophic flooding and wind events to lethal, systemic heatwaves, which demand a comprehensive and coordinated planning response far beyond traditional reactive measures.

Successfully building a truly resilient city requires moving past simple mitigation efforts and adopting a deeply proactive stance, starting with rigorous, high-resolution risk assessment and vulnerability mapping to identify precise failure points within interconnected urban systems.

The implementation phase must utilize a hybrid defense strategy, purposefully combining the strength of hardened, gray infrastructure, such as floodwalls and modernized utility grids, with the sustainable, natural protection provided by restored green and blue ecosystems like wetlands and urban tree canopies.

Critically, resilience planning must have a strong equity focus, prioritizing investments that reduce the extreme vulnerability of low-income neighborhoods and marginalized communities, ensuring access to cooling centers, safe housing, and effective emergency communication.

Securing the massive, necessary long-term capital for adaptation requires innovative financing models, such as specialized climate bonds and value capture mechanisms, coupled with strong, centralized leadership under a dedicated Chief Resilience Officer.

Ultimately, by embracing flexible, adaptive pathways planning—investing in phased, trigger-based solutions rather than rigid mega-projects—cities can ensure they remain capable, viable engines of prosperity, ready to withstand and recover from the inevitable climatic challenges of the coming decades.